Summer 2010 Collaborative Solutions Newsletter:

In this issue: Health Equity and Social Justice

The Center for Health Equity and Social Justice at the

Boston Public

Health Commission

Six key concepts

Community story: The Jamaica Plain Youth Health Equity Collaborative

Principles for Collaborative Solutions and Health Equity

What is new at Tom Wolff & Associates

The Center for Health Equity and Social Justice at the

Boston Public

Health Commission

For my Summer 2010 Newsletter, I’d like to tell you about the

work of the Center for Health Equity and Social Justice at the Boston

Public Health Commission. For the past five years, my work with this

center has been an especially exciting engagement. The simple fact

that a big U.S. city health department has an office named the Center

for Health Equity and Social Justice is surprising, and attests to

the exciting and cutting-edge vision that is being manifested by the

people in this organization. (http://www.bphc.org/programs/healthequitysocialjustice/Pages/Home.aspx)

I began my work with this innovative grassroots program when it was

called Boston REACH 2010 and was a CDC-funded initiative that focused

on racial disparities in breast and cervical cancer survival rates

for Black women in Boston. REACH, which stands for Racial and Ethnic

Approaches to Community Health, provides an excellent example of what

a community can accomplish when it acknowledges the issue of racism

in health and then creates a comprehensive social-change effort to

address inequalities. The outstanding quality of the work of Boston

REACH 2010 allowed the group under the skilled leadership of Nashira

Baril, Meghan Patterson, Courtney Boen and Erline Achille to continue

its work and to expand its scope. The REACH collaborative now receives

CDC funding as a Center of Excellence in the Elimination of Disparities.

In this capacity, the group has built on its initial accomplishments

and has also gone on to fund and support a large number of other communities

in New England that have followed their example and created community

responses to promote health equity.

All of these new efforts are built around the following key concepts:

1.

Addressing institutional and structural racism

The center has an explicit

approach to addressing institutional and structural racism. The Boston

Public Health Commission (BPHC) operates with the understanding that

racism is at the root of racial and ethnic health inequities. Racism

affects health directly by causing stress and anxiety, and it also

affects health indirectly by its impact on the social determinants

of health. Every community that receives a grant, following the lead

of the BPHC itself, engages in a three-day Undoing Racism workshop

(People’s Institute Undoing Racism and

Community Organizing Workshops™) for its core team and for community

members . The BPHC understanding of racism is based on the brilliant

work of Camara Phyllis Jones and her conception of levels of racism. http://www.scribd.com/doc/11917990/Racism-a-Gardeners-Tale.

2. Focus on social determinants of health

As the REACH 2010 group moved to become a Center of Excellence, they

also expanded their approach to include an explicit focus on the

social determinants of health. These social determinans are factors

that have an exceptionally strong and well-demonstrated influence

on health, such as education, socioeconomic status, housing, jobs,

economic opportunity, transportation, food access, safety, environmental

exposures, and so on. These aspects of life actually have a much

more profound impact on people’s overall health than does access

to health care. By looking at community health from the perspective

of the social determinants, groups can examine the ways in which

institutional racism plays out in each realm. As the powerful TV

series Unnatural Causes makes clear, your zip code

may be more important than your genetic code in determining your health (http://www.unnaturalcauses.org).

3. Grassroots community engagement

The center’s approach is

based on a core belief that grassroots involvement is essential to

solving problems. Barbara Ferrer, the Commissioner of Public Health

for the City of Boston, has this to say on the topic:

“The role

of a public health department is to create a space for residents to

come together to define a problem, to define the solutions, and then

enter into a dialogue with us—not the other way around. Not we

define the problem, we define the solution, and then we invite you

in to help us implement the solution, which is what we’re most

comfortable doing. We felt like part of the solution lay in being able

to get a broad-based coalition that would tackle issues like racism.

And that would bring together the provider community with the resident

community to tackle those issues.” (In “Creating

a Health Equity Coalition: Lessons from REACH Boston 2010,” Boston Public

Health Commission, 2010.)

4. Policy change

The project has an explicit focus on creating long-lasting

policy and social change that will endure as a legacy in each participating

community. This follows the lead of the CDC’s new director, Tom

Frieden (see his “A Framework for Public Health Action.”2010). With

this intention in mind, the approach goes beyond creating better understandings

of health disparities and new programs. It also insists that communities

explore policy changes that will improve community health. Examples

include zoning changes to allow for construction of a new supermarket

in a low-income community, or advocating with the legislature to find

summer jobs for teens. All grant-recipient communities are required

to develop and implement policy-based solutions for addressing racism

and the social determinants of health.

5. Focus on a shift from social service to social change

For traditional

nonprofit agencies that work with the center, the greatest challenge

often is found in the explicit shift in focus from social service to

social change. The center is not interested in the creation of new

education programs for Black men at risk of diabetes. Instead, it wants

to promote efforts that will change the institutional racism in housing,

food access,and employment policies that put Black men at higher risk

for diabetes. The goal is to prevent the illness, not provide palliative

treatment. For nonprofits accustomed to delivering social services,

this is a huge change in emphasis.

6. Collaboration

Finally, the center understands that in order to

accomplish systems changes of this large scope a community must

develop a broad-based coalition of residents and agencies that will

work together collaboratively.

Together these six key concepts become a powerful force for transformative

community change.

A new manual describing the work of the BPHC Center

for Health Equity and Social Justice will be available later this summer.

I have had the honor of co-authoring this publication, and it gives

me great joy to be part of this acknowledgment of the center’s trailblazing

work and to put its accomplishments in a form that will help even more

communities achieve health equity. Entitled Creating a Health Equity

Coalition: Lessons from REACH Boston 2010, the manual will be available

at http://www.bphc.org/programs/healthequitysocialjustice/toolsandreports/

Pages/Home.aspx

Another view of this transformative work is available now at :

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TCnDZW-sJXU

References:

Jones, Camara Phyllis. “Levels

of Racism: A Theoretic Framework and a Gardener’s Tale.” American

Journal of Public Health 90, no. 8 (August 2000): 1212–1215. http://www.scribd.com/doc/11917990/Racism-a-Gardeners- Tale.

Frieden, Thomas R. “A Framework for Public Health Action: The

Health Impact Pyramid.” American

Public Health Journal 100, no.

4 (April 2010): 590–595.

Community Story: The Jamaica Plain Youth Health Equity Collaborative

What does support of other communities by the center look like? I’d

like to make the model concrete by telling the story of one local coalition

that is being supported by the center. Jamaica Plain (JP) is a fascinating

neighborhood in Boston. It includes an affluent white community

along with low-income Black and Latino communities — there are

really two JPs, the rich one and the poor one. Accompanying this economic

division are social, and health, inequities. To address the gap, the

Southern JP Health Center has become the sponsor for the development

of the Jamaica Plain Youth Health Equity Collaborative.

The collaborative chose to focus on youth for two big reasons: a strong

base of agencies working with young people already existed, and the

group understood that youth issues are inseparable from community and

family issues. By centering their efforts on health equity for young

people, the group was able to narrow its field of attention (but not

much).

The group’s guiding concept, based on a framework that takes

into account the social determinants of health, envisions the following

life qualities for healthy youth in JP:

- They have high-quality education that helps them achieve their

dreams

- They have meaningful living -wage jobs

- They live in a safe and connected community environment

- They live in high-quality and affordable housing

- They are engaged in high-quality and comprehensive health care

- They have access to high-quality food and an environment that promotes

physical activity

The goals for the JP Youth Health Equity Collaborative were to:

- Involve residents, organizations, and youth

- Examine health disparities

- Identify causes, including social determinants

- Create a common language and framework

- Define and implement programs and change policies

The collaborative is led by a remarkably skilled organizer, Abigail

Ortiz, in partnership with many local agencies that have made a serious

commitment to ensuring that this collaborative succeeds.

In its first year of planning, the collaborative held a series of

interactive Youth Health Equity meetings, called “bucket meetings.” Each

bucket meeting involved a cluster of young people and focused on one

social determinant of health. The purpose of the meetings was to gather

youth perceptions on that social determinant of health. Collaborative

members presented each small group of young people with a case example;

the examples were variations on real stories about community members.

Here’s the type of story the young people were asked to consider: “Claudia

is 16 and living with her mom in public housing in JP. She has been

trying unsuccessfully for two years to get a job. She is always turned

down. She is getting discouraged, and spends more time watching TV

and with her boyfriend who is dealing weed.” The facilitators

then asked the small discussion groups the following questions:

- What are the employment inequities for low-income African American/Latino

youth illustrated by this story?

- What is the role of institutional racism in Claudia’s not

getting a job?

- How will this affect Claudia’s health? I.e., what are the

health impacts of the job situation for low-income African American/Latino

youths?

- And what could we do about this? What possible action steps and

strategies come to mind?

The ”bucket meetings” were well attended by JP young people,

who had no difficulty addressing these questions for each bucket. Young

members of the community implicitly understand the issue of social

determinants of health and institutional racism.

Following the bucket meetings, the collaborative held a Youth Retreat.The

more than 20 young people who participated chose jobs as the ”bucket” area

that they wanted to address first. During the retreat, facilitators

asked the young people to indicate which JP institutions affect the

health of a typical JP youth. As these organizations were mentioned,

they were put on a list. When the list was complete, the facilitators

wrote each named institution on a sheet of paper and asked the young

participants to rate each entity, using colored dots, as being supportive of the health of JP youth, detrimental to their health, or neutral.

The group then stepped back to view the whole and engaged in a discussion

of the map of institutional racism in JP that they had created.

Following the bucket meetings, the collaborative held a Youth Retreat.The

more than 20 young people who participated chose jobs as the ”bucket” area

that they wanted to address first. During the retreat, facilitators

asked the young people to indicate which JP institutions affect the

health of a typical JP youth. As these organizations were mentioned,

they were put on a list. When the list was complete, the facilitators

wrote each named institution on a sheet of paper and asked the young

participants to rate each entity, using colored dots, as being supportive of the health of JP youth, detrimental to their health, or neutral.

The group then stepped back to view the whole and engaged in a discussion

of the map of institutional racism in JP that they had created.

Since those initial, clarifying meetings, the JP Youth Health Equity

Collaborative has been hard at work addressing the issue of jobs for

young people. First, the collaborative has organized a series of work

groups on multiple aspects of youth employment:

- Job development,

- Creating a youth entrepreneurship business, and job training.

- Communications

As part of the collaborative’s work on youth jobs, the group

helped plan and took part in a youth-led protest rally at the State

House urging the legislature to reinstate funds for summer jobs for

young people. The orderly yet powerful rally of 700 young people caught

the attention of both the media and the legislators.

As part of the collaborative’s work on youth jobs, the group

helped plan and took part in a youth-led protest rally at the State

House urging the legislature to reinstate funds for summer jobs for

young people. The orderly yet powerful rally of 700 young people caught

the attention of both the media and the legislators.

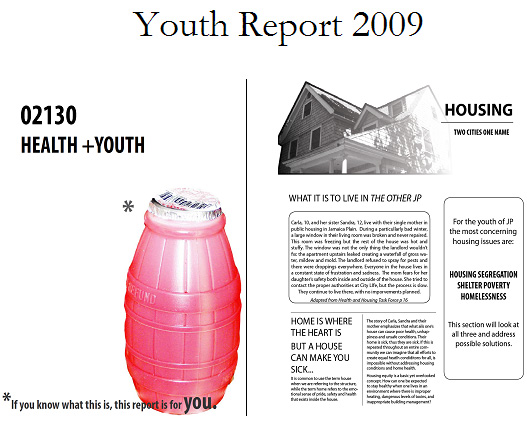

Finally, the project issued a report on health in young people in

JP. Titled “02130 Health and Youth,” it has a picture of

a “teeny” on the cover and the phrase, “If you know

what this is, this report is for YOU.” A “teeny” is

a drink that contains no positive nutritional value—it’s

just sugar, water, and coloring. It is readily available in the stores

that cater to African-American and Latino youth. Stores in the white

neighborhoods of JP sell fresh juice instead.

Thus the “teeny” is

a great symbol of the health inequity campaign. Inside the report,

each social determinant is examined, and the coverage includes youth

stories, youth quotes, data, and ideas on what actions can be taken.

The report, authored by Meghan Wood, is available on the BPHC web site: http://www.bphc.org/programs/healthequitysocialjustice/toolsandreports/

Pages/Home.aspx

Priority areas and key principles

I have recently been struck with how similar the priority areas of

the Center for Health Equity and Social Justice are to the six key

principles I’ve written about in The Power of Collaborative

Solutions.

The center’s work illustrates the six key principles in action.

Let me demonstrate, using examples from some of the center’s

communities that I have had the privilege of working with:

Principles

for Collaborative Solutions and Health Equity

1.Encourage true collaboration as the form of exchange.

The relationship

between the Boston Public Health Commission and the community coalitions,

as articulated by Barbara Ferrer and enacted in the coalition activities,

is truly at the level of collaboration where all participants are “enhancing

the capacity of the other.

2. Engage the full diversity of the community, especially

those most directly affected.

The JP Youth Health Equity Collaborative certainly illustrates having

those most affected by the issues (the JP youth of color) at the table

and setting the agenda.

3. Practice democracy and promote active citizenship

and empowerment.

The Boston REACH coalition begins its meetings by

going around the room with introductions, during which all members

say their names and their neighborhoods. This reflects a conscious

decision to put all members on equal footing and to eliminate fancy

titles and institutions as part of the introductions. In addition,

the Boston REACH Coalition is co-chaired by two community members,

who get coaching and training to guarantee their success in their roles

in collaborating with each other and in guiding the rest of the group

in collaboration.

4. Employ an ecological approach that builds on community

strengths.

The whole approach, emphasizing the social determinants of

health and operating through bucket meetings, is designed to help residents

understand their health in the context of their environment. The success

of this approach becomes clear when women note that the meetings bring

them a sense of huge relief, because they previously always felt that

everyone was blaming them for being the cause of their own illness.The

tag line that your zip code may be more important than your genetic

code in determining your health is the best line I have ever heard

for explaining an ecological approach.

5. Take action by addressing

issues of social change and power on the basis of common vision.

In

Springfield, Massachusetts, the local project is focused on health

equity and food access. Here one major area of attention has involved

zoning changes that will permit the opening of a supermarket in the “food

desert” of the Mason Square area of Springfield.

6. Engage spirituality

as your compass for social change.

I began my work with BPHC by working

with the Boston REACH Coalition when its focus was limited to the incidence

and treatment of breast and cervical cancer in Black women in Boston.

The group of women who worked on leadership, team building, and sustainability

with me were passionate, caring, and committed to making a difference

in their community. They epitomize the spiritual principles of acceptance,

appreciation, deep compassion and interdependence. I am so grateful

to have had the opportunity to know and work with them.

What is New at Tom Wolff & Associates

The release of The Power

of Collaborative Solutions has meant a busy time here at Tom Wolff

and Associates! I’ve been doing book presentations

and signings large and small, and love meeting with people and talking

about collaborative solutions. I was invited to present at the Canadian

Community Psychology Conference in Ottawa in May, and I also held a

book signing there. Then in June I facilitated a two-day workshop on

collaborative solutions for the Third International Community Psychology

Conference, held in Puebla, Mexico.

In the coming months, I’ll be doing talks and readings in, among

other places, Madison Wisconsin; San Diego; Los Angeles (as part of

a Presidential Panel at the APA Convention); Brattleboro,Vermont; Milwaukee,Wisconsin;

and locally here in Massachusetts. Being able to share my experience

with people through the medium of a book release is certainly a learning

experience for me, and I’m enjoying it.

Many of the individual readers I have talked with have made special

mention of the book’s emphasis on spirituality, and how refreshing

and helpful they find that to be. It took a leap of faith to include

the material in the manuscript, because I wasn’t sure how it

would be received. However, to leave it out would have been to overlook

an essential part of community-building for all of us. The role of

spirituality in social change is the area that I hope to spend most

time examining over the coming years.

I have been very pleased to hear from many of my academic colleagues

that they will be adopting The Power of Collaborative Solutions for

their course offerings in the fall. This is happening not only across

the United States but also in Canada, Puerto Rico, and Portugal. I

couldn’t be happier to hear of the widespread enthusiasm for

the book as a resource for students, as well as professionals, around

the world. With enough of us involved, we can build healthy communities,

from the ground up, across the globe.

More information on The

Power of Collaborative Solutions is available

at www.tomwolff.com.